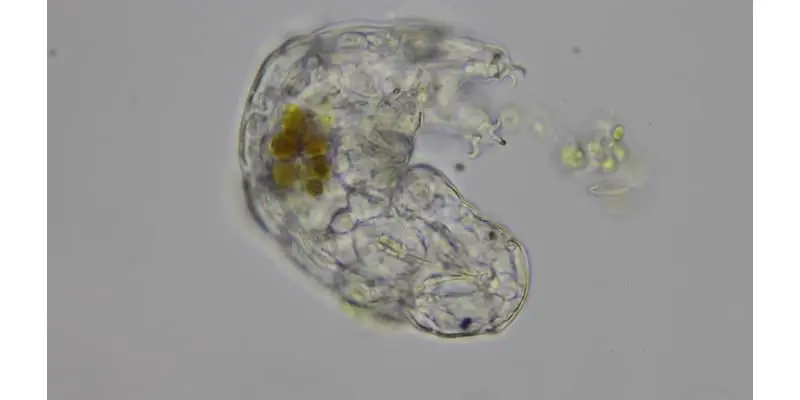

An abundance of life surrounds us all that cannot be seen without a microscope. Imagine an ecosystem as complex as a lavish forest but on a microscopic level. Amongst this microscopic forest, you will find a predator equally as intimidating as a bear: the tardigrade.

Tardigrades, otherwise known as water bears or moss piglets, are eight-legged invertebrates from the phylum Tardigrada that average 0.1 millimeters to 0.5 millimeters in length. They are known for their resilience and ability to live in extreme climates as cold as Antarctica and as hot as volcanic mud. They belong to an inclusive category of animals called extremophiles.

Tardigrades are one of my favorite microorganisms to observe under the microscope and it makes it so much more fun to learn about them and understand what you’re looking at. In this article we will go through some of the basics and things you will need to know about tardigrades to fully appreciate these wonderfully awesome microorganisms!

What is the Structure of a Tardigrade?

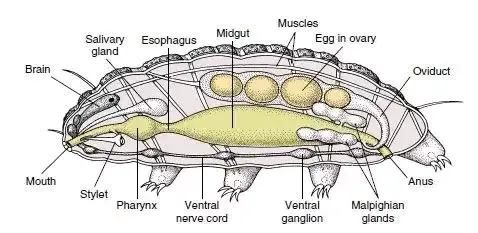

Tardigrades are microscopic creatures with an average length of 0.1mm to 0.5mm. They are bilaterally symmetric and have a total of eight lobopodious legs that are loosely conical in shape. Each of the eight legs is organized into pairs of two and have their own adhesive pads, discs, or claws depending on the species.

All species of tardigrades have an underlying muscular structure. Their bodies are covered with a thick and uncalcified cuticle that resembles that of a grasshopper. The cuticle is oftentimes divided into ornamented dorsal and lateral plates. The dorsal and lateral plates give the tardigrade its renowned ‘fluffy’ or ‘squishy’ appearance. The plates look a lot like fat rolls on an overweight human.

The cuticle is secreted by a cuticular coating, which consists of seven segments of different proteins and chitins. This means that tardigrades undergo molting. Most tardigrades reach maturity after six molting sessions. Some tardigrades that reside outside of saline environments can be very colorful which is dependent upon their diet and cuticle pigmentation.

The body wall of the tardigrade is made up of muscle bands that consist of just one muscle ranging up to several. As we already know, tardigrades are motile thanks to the movement in their legs. Each leg has its own set of independent muscles that operate in cycles to help the tardigrade step. Swimming species of tardigrade expand their cuticle to swim like a jellyfish.

The nervous system of the tardigrade consists of a large and lobed dorsal cerebral ganglion that connects to ventral nerve cords that run the length of the body. These ventral nerve cords are responsible for controlling each pair of legs as it connects through a chain of four ganglia. The exterior of the tardigrade is covered with sensory bristles that should not be confused with setae. They are especially saturated in the anterior and ventral areas. Most species of tardigrade also have clava which are thought to be specialized to transduce a chemical substance into a biological signal. All tardigrades have sockets for eyes, but not all tardigrades have eyes. The eyes consist of five cells in total, only one of them being light-sensitive and pigmented. This means that tardigrades have a sense of sight.

The oral stylets and their organization are dependent upon whether or not the tardigrade is herbivorous or omnivorous. Herbivorous tardigrades have ventral mouths whereas omnivorous and carnivorous tardigrades have terminal mouths. From there, the mouth is attached to a pharynx which has a muscle that is used to suck. The pharynx has salivary glands to aid digestion. Herbivorous tardigrades may have rods within their esophagus which help grind down plant matter, much like molar teeth in humans. The pharynx then leads to the esophagus which transports food matter towards the gut. The gut aids digestion and absorbs nutrients. It then discharges into a secondary gut that leads towards its anus.

How are Tardigrades Classified?

The kingdom Animalia houses the tardigrades and represents a large group of eukaryotic multicellular organisms which are heterotrophic, meaning they seek out their own food from their environment. Unlike plants, the kingdom Animalia is unable to produce its own food.

The large majority of Animalia are motile which allows them to seek out food. There are two major categories of Animalia: vertebrates (having a backbone) and invertebrates (not having a backbone). Tardigrades fall within the second category as they do not have backbones.

From there, tardigrades fall within the phylum Tardigrada. There are over 1,300 species of water bears that make up the phylum Tardigrada. This phylum is controversial as some scientists refer to this phylum Tardigrada as ‘minor phylum’ due to its small size.

To further subdivide Tardigrada, the shape, size, number, and organization of claws is key. There are currently 16 different claw variations known amongst the Tardigrada. They live in habitats such as terrestrial, marine, and freshwater environments. They can be found in virtually every habitat on earth, including extreme habitats such as volcanoes and in the arctic.

There are three main classes of the Tardigrada that comprise tardigrades. The three classes are described below:

- Class: Heterotardigrada – Heterotardigrada represents the most complex and abundant class of tardigrades. It can be further subdivided into two large orders known as Arthrotardigrada and Echiniscoide. From those two orders come several large families including Batillipedidae and Oreellidae. Finally, the families can be broken down into over 50 genera of Tardigrada. Key traits of the class Heterotardigrada include a sensory papilla, which is a rounded protuberance that protrudes from the body. Another characteristic is a toothlike dentate collar on the posterior legs. They have a particularly thick cuticle, much like a grasshopper, that mistakenly gives the tardigrades its fluffy and squishy appearance. Lastly, there is a distinct pore pattern amongst the subspecies.

- Class: Mesotardigrada – Mesotardigrada is a rather inclusive class with only one small order Thermozodia, one small family Thermozodidae, and one single species Thermozodium esakii. This species was discovered deep within a thermal spring in Japan. Important characteristics to note include six claws per foot, a hair-like filament called cirri that is comparable to a barbel of a fish, and do not have a plava. Unfortunately, the thermal spring no longer exists, and no other species have been identified on earth. They are considered extinct.

- Class: Eutaridgrada – Eutaridgrada are separated into two separate orders Parachela and Apochela. These orders are then distributed amongst six families, that include Mineslidae, Macrobiotidae, Hypsibidae, Calohypsibidae, Eohypsibidae and Eohypsibidae. There are 35 genera distributed amongst the six families. Traits that are specific to Eutarigrada include a smooth cuticle, a lack of dorsal plates, and sets of double claws. The gonoducts, or a pair of ducts that lead from a gonad to the exterior in which gametes can travel through, connect to the rectum of this class. Lastly, they do lack lateral limbs.

What do Tardigrades Eat?

Phytophagous tardigrades eat plant matter or marine algae, Bacteriophagous tardigrades are known to be carnivorous and typically eat bacteria, smaller microorganisms, and even other smaller tardigrades. Tardigrades do not produce energy on their own and cannot sustain themselves without consuming organic matter.

Phytophagous is a term coined to describe animals that have adapted to eat plant matter or marine algae. Eating plant matter requires mouthparts that can grind and rasp, so tardigrades that are phytophagous can be identified by their mouths. These tardigrades have terminal mouths. They also possess a special gut flora that allows them to digest plant materials and uptake the nutrients. Most tardigrades that are phytophagous prefer to feast on flowering plants and photosynthetic algae. They suck the juices from algae, lichens, moss, and others.

Bacteriophagous is a term not to be confused with bacteriophages. Bacteriopagous pertains to the predation and consumption of bacteria as part of the tardigrades diet. Lastly, tardigrades may also be carnivorous. They have been observed eating smaller versions of themselves as part of their diet. These tardigrades have ventral mouths.

Tardigrades eat by projecting a stylet, which is a hardened and sharpened anatomical feature in invertebrates that resembles a needle or a nail to pierce into its prey. The stylet is used whether the tardigrade is targeting its own species, algae, or even bacteria. The stylet pierces through the cell wall or membrane and begins to feed on the fluids and juices. Once pierced, the tardigrade pulls its meal into its mouth opening to begin the digestive process.

Tardigrades completely engulf their prey and have been known to entirely engulf organisms as large as rotifers. Other common food sources for tardigrades include other nematodes, snails, mites, oligochaetes (worm-like creatures), spiders, springtails, larvae, and even crustaceous animals. Some species of tardigrade prefer to eat fungus, although this is uncommon.

How do Tardigrades Reproduce?

How a tardigrade reproduces depends on whether it is aquatic or terrestrial. Most terrestrial tardigrades are parthenogenetic or completely self-fertilizing as hermaphrodites. Parthenogenesis is a form of reproduction from an ovum that does not get fertilized. This is a relatively common process in invertebrates and even some plants. Hermaphroditic tardigrades have complete or partial reproductive organs that produce gametes of both sexes. They can self-fertilize without the need for a partner.

Aquatic tardigrades are diocese, which means that male reproductive organs are used in conjunction with female reproductive organs to produce offspring. Sexual reproductive tardigrades each have one gonad regardless of sex. It’s located and protected within the gut. The males each contain a pair of sperm ducts that are attached to a pore that opens near the anal cavity. Females have the same, as well as two additional receptacle openings.

The ovum may be fertilized through direct contact when the male discharges its sperm directly into the receptacle of the female. It could also happen from indirect contact such as when a male discharges its sperm into the water and it settles below where a female is molting. The eggs are laid when the female molts. Some species of tardigrades are known to practice a type of courtship where the male strokes the female with its cirri to convince the female to lay its eggs below, where the male will then discharge its sperm onto.

Tardigrades are not seasonal in their mating habits but tend to only reproduce when conditions are favorable. Females lay several clasps of eggs throughout their two-year lifecycle. Males can reproduce numerous times. If conditions are unfavorable, then tardigrades may undergo cryptobiosis where their metabolic activity is reduced to almost undetectable levels. This helps the tardigrade survive periods of extreme drought.

Development as an egg can take as few as fourteen days or as long as ninety days. How long the egg develops plays a factor in the size of the hatchling. Parthenogenesis can occur in species that are undergoing cyclomorphosis which only occurs when conditions are unfavorable.

Winter hatchlings are unique in that they will group up to keep each other warm. During this time, they are all sexually immature. All hatchlings become simultaneously sexually mature at the same time when temperatures begin to rise again.

Females can lay anywhere from one single egg all the way up to thirty eggs at once. In aquatic species, females eggs are stored in between their cuticle, which is why fertilized eggs are only laid when she molts. Terrestrial species have thick shells that can withstand extreme climates. It’s believed that embryotic tardigrades can also enter cryptobiosis and continue developing once conditions are favorable. Hatchlings use their newly developed stylets to break out of their thick-shelled eggs.

They are oftentimes born without their distinguishable claws and will develop those later in life as their cuticle progresses and molts. A molt can take anywhere from five to ten days but happens much more rapidly in hatchlings. While molting, tardigrades are unable to eat as they also shed a layer of their gut.

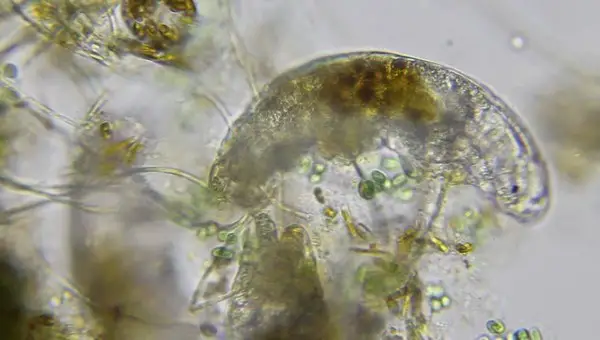

Where do Tardigrades Live?

The habitat of the tardigrade ranges from marine, to freshwater, to terrestrial. They are mostly found in semi-aquatic habitats such as mosses and leaf litter. They can also live in shallow and deep environments. Tardigrades are so unique for their ability to live just about anywhere thanks to their ability to enter a dormant state.

Tardigrades have been found in depths as deep as 4,600 meters in the Mariana Trenches. They’ve been found in freshwater environments as deep as 150 meters. They’ve been observed in habitats as high as 6,000 meters. They’ve been found within glaciers in the Antarctic as well as within lava fields.

A team of Japanese scientists discovered a pile of moss in Antarctica in 1983. They brought the frozen moss back with them to the lab. When unfrozen and studied in 2014, the tardigrades resume life and as if nothing had ever happened. Tardigrades can quite literally be frozen and can pause their metabolic processes under conditions that become favorable again.

Tardigrades are thought to be able to survive a nuclear holocaust thanks to their ability to withstand high levels of radiation and other chemical exposures that are typically harmful to living creatures. A protein unique to tardigrades called Dsup is thought to help the animal live in these extreme radioactive conditions. It is currently being studied in modern medicine for its ability to prevent radiation-related cancers in humans.

In 2007, the European Space Agency put the resilience of tardigrades to the test when they launched a satellite carrying tardigrades into the vacuum of space. They purposely exposed the organisms to cosmic radiation to see if they could survive. Remarkably, when the tardigrades returned to earth and were thawed, several of them had survived.

This is the first species on human record to have survived the vacuum of space and cosmic radiation without protection. It’s theorized that there is even a culture of tardigrade surviving on the moon today. In 2018, a privately funded Israeli project crashed on the moon. Its goal was to launch a robot to conduct scientific exploration missions. Onboard was a culture of tardigrades. It’s possible that the tardigrades have continued to live onboard even today.

The History of Tardigrades

The earliest fossils of the moss piglets date back to the Cretaceous period some 145 million years ago, but scientists believe that tardigrades have been alive for as long as 541 million years. This means that tardigrades have survived all five mass extinctions and are likely to survive the next one as well.

In fact, many scientists believe that tardigrades will outlive the human species altogether. A study published in Scientific Reports predicts that even cataclysmic events like an asteroid impact. There are tardigrades that live so deep in the ocean within the Mariana Trench that they wouldn’t even notice a cataclysmic event like an asteroid.

The survival of five different mass extinctions has afforded the tardigrade immortal-like survival characteristics, including the ability to persist in extreme conditions that other animals would certainly perish in. The tardigrade has persisted through periods of extreme volcanism, glaciations, asteroid strikes, anoxia, and more.

The evolutionary history of the tardigrade is thought to have descended from an even larger tardigrade known as a lobopodian. Many believe that the lobopodian is related to an even more ancient aysheaia, which is a genus of soft-bodied, caterpillar-like microorganisms. An alternate hypothesis suggests that tardigrades descended from tactopoda, a clade of protostomes that includes dinocarids and opabinia, a group of extinct arthropods.

From a scientific perspective, tardigrades were not on the radars of scientists until a German zoologist by the name of Johann August Ephraim Goeze described them in a 1773 publication. In 1977, the creatures were referred to as little water bears for their striking resemblance to bears as we know them. Their chubby bodies and seemingly aloof movements are comparable to that of a bear. Eventually, a biologist and physiologist named Lazzaro Spallanzani named them Tardigrada, which means “slow steppers”.

Spallanzani was originally an Italian Catholic priest who made incredibly important contributions to the study of bodily functions, reproduction tendencies, and animal echolocation. In fact, his work in biogenesis is credited for giving birth to the theory of spontaneous generation, which is the belief that organisms could have developed from inanimate matter.

Are Tardigrades Dangerous to Humans?

Depending on how you look at it, tardigrades are as either cute as a bear or as intimidating as a bear. If tardigrades were the size of real bears, then they would be one of the most terrifying creatures in existence. Thankfully, tardigrades are microscopic and pose no real physical threat to humans.

In fact, tardigrades are as easy to kill as any other harmless microscopic creature despite their ability to live in extreme environments. They are not immortal and not indestructible despite their traits.

You’ve most likely unconsciously eaten tardigrades in the past, which proves that they don’t possess any harmful toxin or poison. Tardigrades have probably been ingested by you unknowingly if you’ve ever eaten a moist piece of vegetable like a misted broccoli. Thankfully, tardigrades are so small and flavorless that you would never have noticed. Unlike washing off pesticides and other grime that collects on vegetables, tardigrades or so small that they are hard to wash off with just a quick rinse.

It’s important to understand that tardigrades cannot withstand the digestive acids and enzymes within your stomach. They certainly all perished once they hit your stomach. In the unlikely scenario that a tardigrade survives passing through your stomach, it will shortly be excreted after it passes through your intestines. Tardigrades do not pose any threat to humans whatsoever. They don’t have the ability to infect a host like a parasite, they don’t have any special toxins or poisons that can make you sick, and they certainly cannot stand up to a human being physically. You can live your life comfortably without having to worry about coming face to face with this bear-like microorganism.

Takeaways

Tardigrades are really awesome organisms to observe under the microscope. They are always moving and climbing over debris and their surroundings. The hardest part about observing Tardigrades under the microscope is that they move so much but if you ever get one or two to slow down or stop for a second you get a great view of all the anatomical structures discussed above. If you are not able to find Tardigrades out in the wild, I would recommend purchasing some live specimens because these are one of the coolest microorganisms I have observed!

References

- https://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/topics/tardigrade/index.html

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/facts/tardigrades-water-bears

- http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/MISC/tardigrade.html

- https://www.mainenewsonline.com/are-tardigrades-dangerous/

- https://www.livescience.com/62720-tardigrade-lifespan.html#:~:text=But%20there%20is%20another%20way,in%20the%20journal%20Scientific%20Reports.

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-05796-x?utm_medium=affiliate&utm_source=commission_junction&utm_campaign=3_nsn6445_deeplink_PID100052172&utm_content=deeplink

- http://jupiter.plymouth.edu/~lts/invertebrates/Primer/text/tardigrada.html

- https://www.scienceabc.com/nature/animals/tardigrades-size-lifespan-facts-water-bears-reproduction-space.html

- https://www.nbcnews.com/mach/science/what-tardigrade-ncna1065771

- https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Tardigrada/

- https://elifesciences.org/digests/47682/how-tardigrades-survive-the-extreme#:~:text=Tardigrades%2C%20also%20known%20as%20water,to%20other%20forms%20of%20life.

- https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2019/8/6/20756844/tardigrade-moon-beresheet-arch-mission

- https://www.mainenewsonline.com/are-tardigrades-dangerous/